EVOGENIO®

- Evolutionäre Kunst

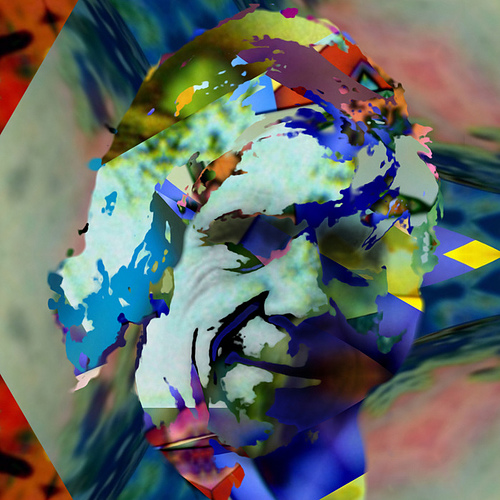

- William D. Hamilton

Ein Click auf das Portrait führt zur Population der Evolutionären Portraitkunst erstellt von Dr. Günter Bachelier

William Donald „Bill“ Hamilton (* 1. August 1936 in Kairo, Ägypten; † 7. März 2000) war ein englischer Biologe, der Forschungen auf dem Gebiet der Ethologie, Evolutionsbiologie, Zoologe und Genetik betrieb. Er wurde berühmt für seine theoretische Arbeit, welche die genetische Grundlage für die Existenz der Verwandtenselektion (kin selection) lieferte. Er kann als ein Vorläufer der Soziobiologie angesehen werden, die von Edward Osborne Wilson begründet wurde.

Leben

Frühe Jahre

Hamilton wurde 1936 in Kairo als zweitältestes von sechs Kindern geboren. Sein Vater, A. M. Hamilton war ein in Neuseeland geborener Ingenieur, und seine Mutter, B. M. Hamilton, war eine Ärztin.

Die Familie Hamilton zog nach Kent als Bill ein Junge war. Während des Zweiten Weltkrieges war er nach Edinburgh evakuiert. Er interessierte sich früh für Naturkunde und verbrachte seine Freizeit damit Schmetterlinge und andere Insekten zu sammeln. 1946 entdeckte er das Buch Butterflies (Schmetterlinge) von E.B. Ford, welches ihn in die Prinzipien der Evolution einführte.

Er wurde an der Tonbridge Schule erzogen, wo er im Schulhaus wohnte. Als 12-Jähriger wurde er ernsthaft verwundet, als er mit Sprengstoff spielte, den sein Vater übriggelassen hatte, als er Handgranaten für die Heimatverteidigung während des Zweiten Weltkrieges herstellte. Der Unfall hätte ihm wahrscheinlich das Leben gekostet, wäre seine Mutter nicht Ärztin gewesen. Man musste ihm Finger an der rechten Hand amputieren und es benötigte sechs Monate bis zu seiner Genesung.

Während seiner ersten Studienjahre am St John’s College, Universität Cambridge mit Abschluss (B. S.) 1960, wurde er wesentlich beeinflusst von Ronald Fishers Buch The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, welches eine mathematische Grundlage für Evolutionsgenetik lieferte. In der Hauptsache wandte es sich gegen die Vorstellungen der Gruppenselektion.

Hamiltons Regel

Er machte seine Doktorarbeit 1968 während er am University College London und an der London School of Economics and Political Science immatrikuliert war, über die Grundsätze, die später als 'Hamiltons Regel' der Gesamtfitness bekannt wurden. Seine Arbeiten über dieses Thema werden heute weltweit zitiert.

Die Gesamtfitness eines Lebewesens kann gemessen werden als die Anzahl der eigenen Gene, die an die nachfolgende Generation weitergegeben wird. Sie setzt sich zusammen aus

a) der direkten Fitness, den eigenen Genen in den eigenen Nachkommen, die es ohne fremde Hilfe produzieren konnte und

b) der indirekten Fitness, den eigenen Genen, die durch seine Hilfe zusätzlich an fremde Nachkommen weitergegeben wurden.

Nach John Maynard Smith existiert neben der Weitergabe der Gene durch die eigene Fortpflanzung (direkte Fitness) außerdem die Möglichkeit, Verwandten bei deren Nachkommenproduktion zu helfen (indirekte Fitness). Da diese Lebewesen zum Teil dieselben Gene besitzen wie das helfende Individuum, fördert dieses durch sein Helferverhalten die Weitergabe des eigenen Erbguts (Verwandtenselektion, „kin selection“). Dieser Altruismus ist nur dann erfolgreich und breitet sich aus, wenn der Nutzen für denjenigen, der das altruistische Verhalten zeigt, größer ist als die Kosten, die er dafür investieren muss (Hamiltons Regel).

Mathematisch ausgedrückt muss das Verhältnis von Nutzen (B) zu Kosten (C) größer sein als eins dividiert durch den Verwandtschaftsgrad.

beziehungsweise

beziehungsweise

mit B: Nutzen (benefit); C: Kosten (cost); r: Verwandtschaftskoeffizient (relatedness)

Beispiel: Ein Tier, das durch seine Hilfe auf zwei eigene Nachkommen verzichtet (C = 2), dafür aber einem Geschwister (Verwandtschaftsgrad zwischen Geschwistern bei diploiden Organismen (r = 0,5) hilft, fünf zusätzliche Nachkommen (B = 5) zu produzieren, hat eine höhere Gesamtfitness als ein Tier, das „egoistisch“ nicht hilft.

Unter Einbeziehung der verschiedenen Verwandtschaftsgrade zum Empfänger und zu den eigenen Nachkommen ergibt sich folgende Formel:

rB: Verwandtschaftsgrad des Gebers zum Empfängers; rC: Verwandtschaftsgrad des Gebers zu den eigenen Nachkommen

Die obige Formel trug wesentlich zum Verständnis des Altruismus bei sozialen Insekten bei. Aufgrund der ungewöhnlichen Haplodiploidie sozialer Insekten (Ameisen, Bienen und Wespen) ergibt sich bei Vollschwestern eines Nestes ein Verwandtschaftskoeffizient von 0,75 miteinander, mit ihren Vollbrüdern 0,25. Mit ihren eigenen Nachkommen sind diese Arbeiterinnen jedoch nur zu 50 % (r = 0,5), also weniger als mit den Schwestern, verwandt. Als Folge ist es für Arbeiterinnen sozialer Insekten, wenn die Königin sich nur einmal gepaart hat, genetisch vorteilhafter, eigene Schwestern als Töchter aufzuziehen.

Außergewöhnliche Geschlechterverhältnisse

Zwischen 1964 und 1978 war Hamilton Dozent am Imperial College London. Dort veröffentlichte er einen Aufsatz in Science über 'Außergewöhnliche Geschlechterverhältnisse'. Ronald A. Fisher hatte 1930 ein Modell vorgeschlagen, warum das normale Geschechterverhältnis beinahe immer 1 : 1 ist und dass ungewöhnliche Verhältnisse wie bei den Wespen einer Erklärung bedürfen. Dies eröffnete ein ganz neues Forschungsgebiet. Der Aufsatz führte das Konzept der unschlagbaren Strategie ein, welches John Maynard Smith und George R. Price zur evolutionär stabilen Strategie ESS weiterentwickelten, einem Konzept der Spieltheorie, das nicht nur auf die Evolutionsbiologie beschränkt war.

Hamilton wurde als schlechter Dozent betrachtet. Dieser Mangel beeinträchtigte nicht die Popularität seiner Arbeit, da sie durch Richard Dawkins 1976 in Dawkins Buch Das egoistische Gen bekanntgemacht wurde.

1976 heiratete er Christine Friess, sie hatten drei Töchter, Helen, Ruth und Rowena. Später ließen sie sich scheiden.

Er war Gastprofessor an der Harvard Universität und verbrachte später neun Monate bei der Royal Society und der Royal Geographic Society 'Xavantina-Cachimbo Expedition' als Gastprofessor an der Universidade de São Paulo.

Von 1978 an war er Professor für Evolutionbiologie an der University of Michigan. Gleichzeitig wurde er als ausländisches Ehrenmitglied der American Academy of Arts and Sciences gewählt. Seine Ankunft löste Proteste und Sitzstreiks unter Studenten aus, die seine Ansichten in der Soziobiologie nicht teilten.

Jagd der Roten Königin

Er veröffentlichte ebenfalls die Rote Königin-Theorie der Evolution der Geschlechtlichkeit. Dies wurde nach einer Figur in Alice hinter den Spiegeln von Lewis Carroll benannt. Hamilton sagte voraus, dass Geschlechtlichkeit sich deshalb herausgebildet habe, weil dadurch immer neue Gen-Kombinationen entstanden - die geschlechtlichen Organismen waren immer wieder ihren Parasiten gegenüber im Vorteil.

Zurück in England [Bearbeiten]

Im Jahre 1980 wurde er zum Mitglied der Royal Society gewählt, und 1984 wurde er Royal Society Research Professor am New College, Universität Oxford, Abteilung Zoologie, wo er bis zu seinem Tode blieb.

Von 1994 an lebte er mit Maria Luisa Bozzi, einer italienischen Schriftstellerin, zusammen.

Zur Entstehung von AIDS

Während der 1990er Jahre wurde Hamilton zunehmend überzeugt davon, dass die Herkunft der AIDS-Epidemie in verseuchtem Serum bei der Polio-Schluckimpfung (engl. Oral Polio Vaccines, abgekürzt OPV) in Afrika während der 1950er Jahre lag (die OPV-AIDS-Hypothese). Briefe von Hamilton an Science wurden von der Zeitschrift zurückgewiesen, unter der Klage, dass das medizinische Establishment gegen die OPV-AIDS-Hypothese vorgehen würde.

Um Beweise für die OPV-AIDS-Hypothese zu erhalten, wollte man den natürlichen Pegel des Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) in Primaten feststellen. Dazu wagte sich Hamilton mit zwei anderen Kollegen in die kriegszerrissene Demokratische Republik Kongo, wo er sich mit Malaria ansteckte. Er wurde nach Hause gebracht und verbrachte sieben Wochen im Krankenhaus, bevor er starb.

Postscript

Eine weltliche Gedenkfeier (er war ein Atheist) wurde am Samstag 1. Juli 2000 in der Kapelle von New College Universität Oxford abgehalten, organisiert von Richard Dawkins.

Auszeichnungen

- 1978 Ausländisches Ehrenmitglied der American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1980 Mitglied der Royal Society von London

- 1982 Newcomb Cleveland Prize der American Association for the Advancement of Science

- 1988 Darwin-Medaille der Royal Society von London

- 1989 Linné-Medaille der Linnean Society of London

- 1991 Frink Medal der Zoologischen Gesellschaft von London

- 1992/3 Wanderpreis der Universität Bern

- 1993 Crafoord-Preis der Schwedische Akademie der Wissenschaften

- 1993 Kyoto Prize der Inamori Foundation

- 1995 Fyssen Prize der Fyssen Fondation

Zur Zeit (2004) wird eine biografische Denkschrift für die Royal Society vorbereitet.[1]

Werke

- W.D. Hamilton (1963): The evolution of altruistic behavior. — The American Naturalist 97: 354–356.

- W.D. Hamilton (1964) The genetical evolution of social behaviour I and II. — Journal of Theoretical Biology 7: 1-16 and 17-52. pubmed I pubmed II

- W.D. Hamilton (1966) The moulding of senescence by natural selection. — Journal of Theoretical Biology 12: 12–45.

- W.D. Hamilton (1967) Extraordinary sex ratios. Science 156: 477-488. pubmed JSTOR

- W.D. Hamilton (1970) Selfish and spiteful behaviour in an evolutionary model. — Nature 228:1218–1220.

- W.D. Hamilton (1971) The geometry of the selfish herd. — Journal of Theoretical Biology 31: 295–311.

- W.D. Hamilton (1972) Altruism and related phenomena, mainly in social insects. — Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3: 193–232.

- W.D. Hamilton (1975) Innate social aptitudes of man: an approach from evolutionary genetics. in R. Fox (ed.), Biosocial Anthropology, Malaby Press, London, 133-53.

- W.D. Hamilton (1980) Sex versus non-sex versus parasite. — Oikos 35: 282–290.

- Axelrod, R. und W.D. Hamilton (1981) The evolution of co-operation Science 211: 1390-6 Pubmed, JSTOR

- W.D. Hamilton & Zuk, M.: (1982) Heritable true fitness and bright birds — a role for parasites. — Science 218: 384–387.

- W.D. Hamilton (1996) Narrow Roads in Gene Land vol. 1 Oxford University Press,Oxford. ISBN 0716745305

- W.D. Hamilton (2000) My intended burial and why, Ethology Ecology and Evolution 12 111-122 link

- W.D. Hamilton (2002) Narrow Roads in Gene Land vol. 2 Oxford University Press,Oxford. ISBN 0198503369

- A.W.F. Edwards (1998), Notes and Comments. Natural selection and sex ratio: Fisher's sources. American Naturalist 151: 564-569

- Ronald Fisher (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- E.B. Ford (1945) New Naturalist 1: Butterflies. Collins: London.

- John Maynard Smith und George R. Price (1973) The logic of animal conflict. Nature 146: 15—18.

Einzelreferenzen

Weblinks

- Obituaries and reminiscences

- Centro Itinerante de Educação Ambiental e Científica Bill Hamilton (The Bill Hamilton Itinerant Centre for Environmental and Scientific Education) (in Portuguese)

- Non-mathematical excerpts from Hamilton 1964

- W.D. Hamilton's work in game theory

- polio vaccines and AIDS

Quelle (05.2008): http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_D._Hamilton

William Donald Hamilton, F.R.S. (1 August 1936 — 7 March 2000) was a British evolutionary biologist, considered one of the greatest evolutionary theorists of the 20th century.[1] From 1984 to his death in 2000, he was the Royal Society Research Professor at Oxford University. Hamilton became famous for his theoretical work expounding a rigorous genetic basis for the existence of kin selection. This insight was a key part of the development of a gene-centric view of evolution, and he can therefore be seen as one of the forerunners of the discipline of sociobiology popularized by E. O. Wilson. Hamilton also published important work on sex ratios and the evolution of sex.

Biography

Early life

Hamilton was born in 1936 in Cairo, Egypt, the second eldest of six children. His father A. M. Hamilton was a New Zealand-born engineer. His mother B. M. Hamilton was a medical doctor.

The Hamilton family settled in Kent. During the Second World War he was evacuated to Edinburgh. He had an interest in natural history from an early age and would spend his spare time collecting butterflies and other insects. In 1946 he discovered E.B. Ford's New Naturalist book Butterflies, which introduced him to the principles of evolution by natural selection, genetics and population genetics.

He was educated at Tonbridge School, where he was in the School House. As a 12-year old he was seriously injured while playing with explosives his father had left over from when he made hand grenades for the Home Guard during the Second World War, an accident that probably would have killed him had his mother not been medically qualified. A thoracotomy in King’s College Hospital saved his life, but the explosion left him with amputated fingers on his right hand and scarring on his body — he took six months to recover.

Hamilton stayed on an extra term at Tonbridge in order to complete the Cambridge entrance examinations, and then travelled in France. He then completed two years of national service. As an undergraduate at St. John's College, he was uninspired by the fact that there "many biologists hardly seemed to believe in evolution". Nevertheless, he came across Ronald Fisher's book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection; Fisher lacked standing at Cambridge as he was viewed only as a statistician. Hamilton wrote on a postcard to his sister Mary on the day he found the book, excited by its chapters on eugenics. In earlier chapters, Fisher provided a mathematical basis for the genetics of evolution. Working through the stodgy prose, Hamilton later blamed Fisher's book for his getting only a 2:1 degree.

Hamilton's rule

Hamilton having various ideas and problems enrolled on an MSc course in human demographics at the London School of Economics (LSE), under Norman Carrier who secured for him various grants. Later when work became more mathematical and then genetical, he had his supervision transferred to John Hajnal of the LSE and Cedric Smith of University College London (UCL).

Both Fisher and J. B. S. Haldane had seen a problem in how organisms could increase the fitness of their own genes by aiding their close relatives, but not recognised its significance or properly formulated it. Hamilton worked through several examples, and eventually realised that the number that kept falling out of his calculations was Sewall Wright's coefficient of relationship. Thus became Hamilton's rule. Briefly, the rule is that a costly action should be performed if:

Where C is the cost in fitness to the actor, R the genetic relatedness between the actor and the recipient and B is the fitness benefit to the recipient. Fitness costs and benefits are measured in fecundity. His two 1964 papers entitled The Genetical Evolution of Social Behavior are now widely referenced.

The proof and discussion of its consequences however involved heavy mathematics, and was passed over by two reviewers. The third, John Maynard Smith, did not completely understand it either, but recognised its significance; this passing over would later lead to friction between Hamilton and Maynard Smith, Hamilton feeling that Maynard Smith had held his work back to claim credit for the idea himself. The paper was printed in the relatively obscure Journal of Theoretical Biology, and when first published was largely ignored. The significance of it gradually increased, to the point where they are routinely cited in biology books. To date, however, there have been no empirical studies that have calculated values for R, B, and C to determine if Hamilton's rule is ever satisfied in nature; as such, even after more than 40 years, the theory remains unproven, though predictions based upon the theory are largely supported.

A large part of the discussion related to the evolution of eusociality in insects of the order Hymenoptera (ants, bees and wasps) based on their unusual haplodiploid sex-determination system. This system means that females are more closely related to their sisters than to their own (potential) offspring. Thus, Hamilton reasoned, a "costly action" would be better spent in helping to raise their sisters, rather than reproducing themselves.

Extraordinary sex ratios

Between 1964 and 1978 Hamilton was a lecturer at Imperial College London. Whilst there he published a paper in Science on "extraordinary sex ratios". Fisher (1930) had proposed a model as to why "ordinary" sex ratios were nearly always 1:1 (but see Edwards 1998), and likewise extraordinary sex ratios, particularly in wasps, needed explanations. Hamilton had been introduced to the idea and formulated its solution in 1960 when he had been assigned to help Fisher's pupil A.W.F. Edwards test the Fisherian sex ratio hypothesis. Hamilton combined his extensive knowledge of natural history with deep insight into the problem, opening up a whole new area of research.

The paper was also notable for introducing the concept of the "unbeatable strategy", which John Maynard Smith and George R. Price were to develop into the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS), a concept in game theory not limited to evolutionary biology. Price had originally come to Hamilton after deriving the Price equation, and thus rederiving Hamilton's rule. Maynard Smith later peer reviewed one of Price's papers, and drew inspiration from it. The paper was not published but Maynard Smith offered to make Price a co-author of his ESS paper, which helped to improve relations between the men. Price committed suicide in 1975, and Hamilton and Maynard Smith were among the few present at the funeral.

Hamilton was regarded as a poor lecturer. This shortcoming would not affect the popularity of his work, however, as it was popularised by Richard Dawkins in Dawkins' 1976 book The Selfish Gene.

In 1966 he married Christine Friess and they were to have three daughters, Helen, Ruth and Rowena. 26 years later they amicably separated. Recently he declared himeslf as gay,

Hamilton was a visiting professor at Harvard University and later spent nine months with the Royal Society's and the Royal Geographic Society's Xavantina-Cachimbo Expedition as a visiting professor at the University of São Paulo.

From 1978 Hamilton was Professor of Evolutionary Biology at the University of Michigan. Simultaneously, he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His arrival sparked protests and sit-ins from students who did not like his association with sociobiology. There he worked with the economist Robert Axelrod on the prisoner's dilemma.

Chasing the Red Queen

Hamilton was an early proponent of the Red Queen theory of the evolution of sex,[2] first proposed by Leigh Van Valen. This was named for a character in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass, who is continuously running but never actually travels any distance:

- "Well, in our country," said Alice, still panting a little, "you'd generally get to somewhere else—if you ran very fast for a long time, as we've been doing."

- "A slow sort of country!" said the Queen. "Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!" (Carroll, pp. 46)

This theory hypothesizes that sex evolved because new and unfamiliar combinations of genes could be presented to parasites, preventing the parasite from preying on that organism—species with sex were able to continuously "run away" from their parasites. Likewise, parasites were able to evolve mechanisms to get around the organism's new set of genes, thus perpetuating an endless race.

Back in Britain

In 1980 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1984 he was invited by Richard Southwood to be the Royal Society Research Professor at New College, Oxford, Department of Zoology, where he remained until his death.

From 1994 Hamilton found companionship with Maria Luisa Bozzi, an Italian science journalist and author.

On the Origin of HIV

During the 1990s Hamilton became increasingly convinced by the controversial argument that the origin of the HIV virus lay in oral polio vaccines (the OPV AIDS hypothesis) in Africa during the 1950s. Letters by Hamilton to Science were rejected by the journal, amid accusations that the medical establishment were ranging against the OPV hypothesis.

To find indirect evidence of the OPV hypothesis by assessing natural levels of SIV in primates, he and two others ventured on a field trip to the war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo, where he contracted malaria. He was rushed home and spent six weeks in hospital before dying from a cerebral haemorrhage.

Postscript

A secular memorial service (he was an atheist) was held at the Chapel of New College, Oxford on Saturday 1 July 2000, organised by Richard Dawkins.

His body was interred in Wytham Woods. He however had written an essay on My intended burial and why in which he wrote:[3]

| “ | I will leave a sum in my last will for my body to be carried to Brazil and to these forests. It will be laid out in a manner secure against the possums and the vultures just as we make our chickens secure; and this great Coprophanaeus beetle will bury me. They will enter, will bury, will live on my flesh; and in the shape of their children and mine, I will escape death. No worm for me nor sordid fly, I will buzz in the dusk like a huge bumble bee. I will be many, buzz even as a swarm of motorbikes, be borne, body by flying body out into the Brazilian wilderness beneath the stars, lofted under those beautiful and un-fused elytra which we will all hold over our backs. So finally I too will shine like a violet ground beetle under a stone. | ” |

The second volume of his collected papers was published in 2002.

Social evolution

The field of social evolution, of which Hamilton's rule has central importance, is broadly defined as being the study of the evolution of social behaviours, i.e. those that impact on the fitness of individuals other than the actor. Social behaviours can be categorized according to the fitness consequences they entail for the actor and recipient. A behaviour that increases the direct fitness of the actor is mutually beneficial if the recipient also benefits, and selfish if the recipient suffers a loss. A behaviour that reduces the fitness of the actor is altruistic if the recipient benefits, and spiteful if the recipient suffers a loss. This classification was first proposed by Hamilton in 1964.[citation needed]

Through his collaboration with Hugh N. Comins and Bob May on evolutionarily stable dispersal strategies, Hamilton acquired an Erdős number of 5.[citation needed]

Awards

- 1978 Foreign Honorary Member of American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- 1980 Fellow of the Royal Society of London

- 1982 Newcomb Cleveland Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

- 1988 Darwin Medal of the Royal Society of London

- 1989 Scientific Medal of the Linnean Society

- 1991 Frink Medal of Zoological Society of London

- 1992/3 Wander Prize of the University of Bern

- 1993 Crafoord Prize of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- 1993 Kyoto Prize of the Inamori Foundation

- 1995 Frissen Prize of the Fyssen Foundation

Biographies

- Alan Grafen has written a biographical memoir for the Royal Society. See http://users.ox.ac.uk/~grafen/cv/WDH_memoir.pdf

- A book is also in press: Segerstråle, U. 2007 Nature's oracle: an intellectual biography of evolutionist W. D. Hamilton. Oxford University Press. See http://www.oup.com/uk/catalogue/?ci=9780198607274

Works

Collected papers

Hamilton started to publish his collected papers starting in 1996, along the lines of Fisher's collected papers, with short essays giving each paper context. He died after the preparation of the second volume, so the essays for the third volume come from his coauthors.

- Hamilton, W.D. (1996) Narrow Roads of Gene Land vol. 1: Evolution of Social Behaviour Oxford University Press,Oxford. ISBN 0-7167-4530-5

- Hamilton, W.D. (2002) Narrow Roads of Gene Land vol. 2: Evolution of Sex Oxford University Press,Oxford. ISBN 0-19-850336-9

- Hamilton, W.D. (2005) Narrow roads of Gene Land, vol. 3: Last Words (with essays by coauthors, ed. M. Ridley). Oxford University Press, Oxford. ISBN 0-19-856690-5

Significant papers

- Hamilton, W.D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour I and II. — Journal of Theoretical Biology 7: 1-16 and 17-52. pubmed I pubmed II

- Hamilton, W.D. (1967). Extraordinary sex ratios. Science 156: 477-488. pubmed JSTOR

- Hamilton, W.D. (1971). Geometry for the selfish herd. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 31: 295-311.

- Hamilton, W.D. (1975). Innate social aptitudes of man: an approach from evolutionary genetics. in R. Fox (ed.), Biosocial Anthropology, Malaby Press, London, 133-53.

- Axelrod, R. and W.D. Hamilton (1981) The evolution of co-operation Science 211: 1390-6 Pubmed, JSTOR

Other references

- Edwards, A.W.F. (1998), Notes and Comments. Natural selection and sex ratio: Fisher's sources. American Naturalist 151: 564-569

- Fisher, R.A. (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Ford E.B. (1945) New Naturalist 1: Butterflies. Collins: London.

- Maynard Smith, J. and G.R. Price (1973) The logic of animal conflict. Nature 146: 15—18.

- Dawkins, R. (1989), The Selfish Gene, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

- Madsen, E.A., Tunney, R., Fieldman, G., Plotkin, H.C., Dunbar, R.I.M., Richardson, J.M., & McFarland, D. (2006) Kinship and altruism: A cross-cultural experimental study. British Journal of Psychology [1]

Cited references

- ^ Obituary by Richard Dawkins - The Independent - 10 March 2000

- ^ The Red Queen Hypothesis at Indiana University. Quote: "W.D. Hamilton and John Jaenike were among the earliest pioneers of the idea."

- ^ Hamilton, W.D. (2000) My intended burial and why, Ethology Ecology and Evolution 12 111-122 PDF

Other references

- Obituaries and reminiscences

- Royal Society citation

- Truth and Science: Bill Hamiltonís legacy

- Centro Itinerante de Educação Ambiental e Científica Bill Hamilton (The Bill Hamilton Itinerant Centre for Environmental and Scientific Education) (in Portuguese)

- Non-mathematical excerpts from Hamilton 1964

- "If you have a simple idea, state it simply" a 1996 interview with Hamilton

Game Theory

AIDS

Quelle (05.2008): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._D._Hamilton